|

To me style is just the outside of content, and content the inside of style, like the outside and the inside of the human body - both go together, they can't be separated. - JLG |

At some point in late 2020 I decided to address my most significant cinematic blindspot and finally become acquainted with Monsieur Jean-Luc Godard. Being well aware of his role in shaping modern cinema and extraordinary breadth of his output, I wasn't quite sure where to begin so I decided to just watch his films in chronological order; all of his theatrical features and as much of his television and video work as I could get my hands on. Unsurprisingly, the project is ongoing: much of his work is incredibly difficult to track down, after all, and he isn't exactly an every night before bed kind of director. But discovering him on his own terms, or as close to it as I've been able to manage, has been an incredibly rewarding experience. I find that it is always ideal to watch a director's films chronologically whenever possible, as it affords one the opportunity to trace their artistic evolution, but I'm not sure I can think of another director who benefits as much from it as Godard. He is such an autobiographical filmmaker, perhaps the most autobiographical filmmaker we've ever had. It really feels like he makes films as a way to resolve whatever artistic, emotional, political or philosophical conflicts (though he would likely say they are one ansd the same) he happens to be grappling with at the time. Sometimes he will riff on the same idea for years until he feels he gets it right, other times he will abandons long-running themes entirely because they no longer interest him. But if there is a grand unifying element to all of his films throught his many periods it appears to be a profound love for the boundless possibilities of narrative cinema and a continual disappointment at how infrequently those possibilities are explored.

I've been writing some of my thoughts down on Letterboxd after every new Godard film but I figure I might as well compile them here. My thoughts on each film will be taken mostly verbatim from my Letterboxd reviews (if one can call them that, hah!) with only a few modifications for the sake of spelling or clarity wherever I deem them necessary. I will also try to keep them grouped by artistic period as best as I can, though I may have to split some of the posts into multiple parts due to length. Bear in mind that the for the first couple of films I wrote down little more than just general, overall impressions. As much as I liked him from the get-go, it took me a few films to 'get' Godard and even longer to be able to express my thoughts in greater detail.

I honestly have no idea whether these posts will be of any use to anyone or if they are just an excercise in narcicism but, without any further ado...

|

| 1960 |

As exemplified by its two leads, ill-fated lovers who are completely oblivious to anything but their own desires, patterning themselves after their favorite actors and exchanging half-baked banalities as if they were the most profound observations from the deepest recesses of their souls, 'Breathless' is a film that is all about the exuberance of youth and the pleasures of cinema.

That it is almost indescribably light and airy, and that there is little weight to the action or its consequences, is all the more to its credit: this is a film of inside jokes, digressions, allusions and brazen nonchalance. It takes nothing seriously, certainly not itself, and in its breezy playfulness it managed to change the world.

|

| 1961 |

Godard's follow-up to 'Breathless' is just as light but not nearly as exciting because, for all of its whimsy, it feels deliberate and studied when it comes to its playfulness. There is something to be said, for example, about a musical where, for the first hour, the music never really comes together because it keeps constantly cutting in and out due to the intrusion of ambient sounds, character dialogue or on-screen action. Godard appears to be carefully deconstructing the many uses of music on film (diegetic, commenting on the action, heightening emotions, tying transitions together, etc...) by revealing the artifice, which is admirable enough, yet the overall effect borders on the insufferable. Not only is the music itself somewhat irritating to begin with, but the constant, calculated interruptions keep it from attaining any kind of rhythm. What we are left with, for the bulk of the film, is the same tiresome fragments from the same motif being repeated ad nauseum at seemingly random intervals.

Thankfully, there are enough terrific set pieces that, even if they never come together into much of a cohesive whole, make the film worth watching, such as the delightful moment where Angela and Emile repeat each other's words and movements, like Rogers and Astaire dancing, but without music, the playful use of book titles to communicate, a revelation of potential infidelity that is almost entirely devoid of dialogue, Anna Karina's naturalistic performance and the innumerable references to films, filmmakers and the cinema itself.

|

| 1962 |

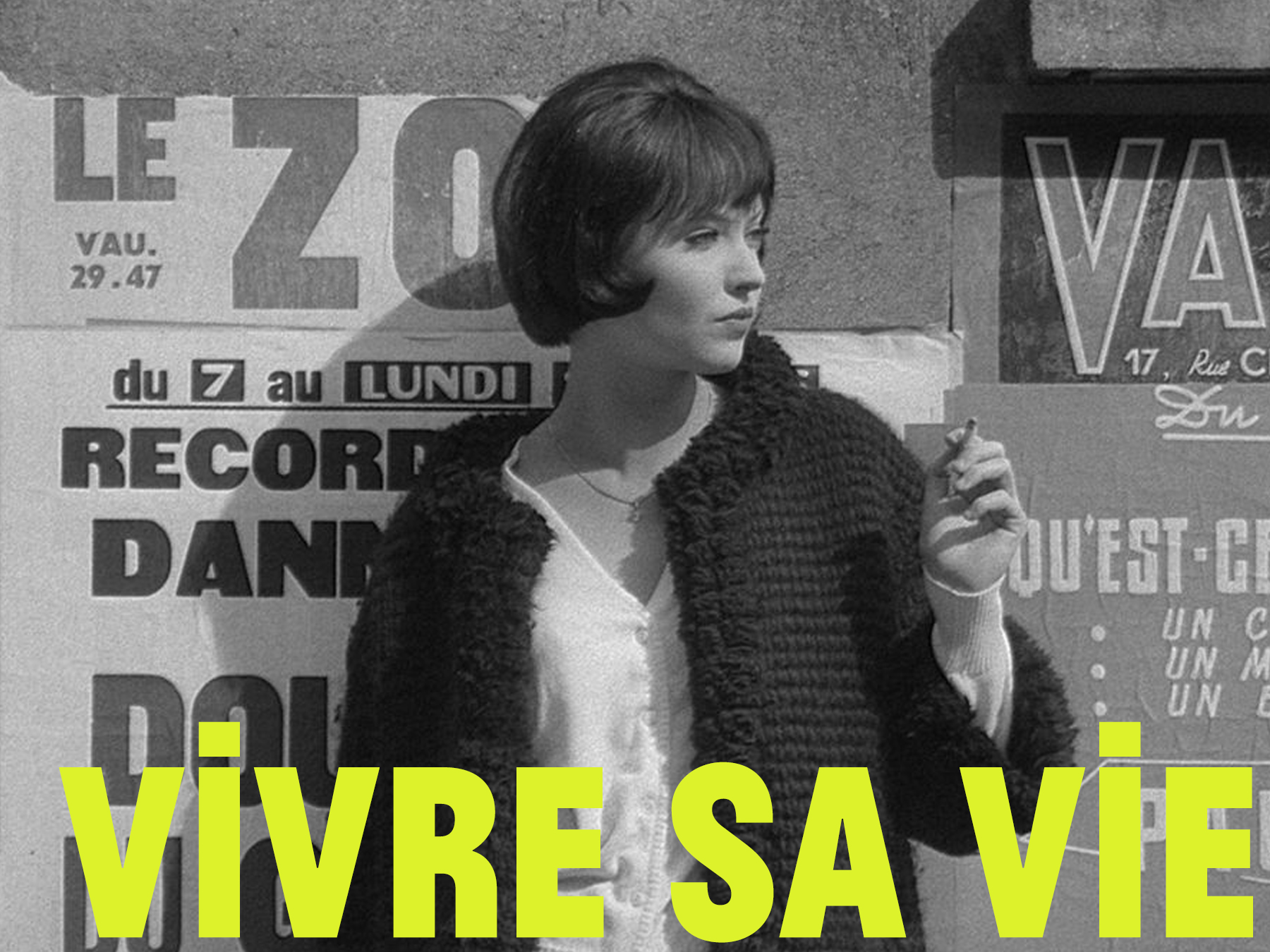

Godard's "Vivre Sa Vie" contains a level of emotional maturity and an interest in human nature that had not even been hinted at in "Breathless" or "Un Femme Est Un Femme". His interest in meta-cinema and Brechtian Verfremdungseffekt remains entirely unabated, but now the references and distancing techniques are motivated primarily by the screenplay: framing Nana from behind during the opening scene only highlights her impenetrability, the sequence where she watches "The Passion of Joan of Arc" in a movie theater actually highlight her struggles, the clinical voiceover which discusses the ins and outs of sex work serves to brutally deglamorize it. Even the camera, though self-conscious as ever, is no longer handheld and looks to serve the characters at least as much as itself.

"Vivre Sa Vie" is a film that, as an intertextual exploration of film and filmmaking, could fit well perfectly alongside Godard's previous output but which simultaneously operates as a profoundly moving character study about a deeply human figure. Nana is Godard's iteration of a fallen woman, very much in the style of Mizoguchi, and Anna Karina is nothing less than a revelation in the role. Every ounce of the ebullient joie de vivre she radiated in "Un Femme Est Un Femme" has been replaced by a pathological aimlessness and an unfathomable melancholy that seem to emanate from the innermost depths of her being. In all of her complexity and contradictions, she provides the film with a soul.

|

| 1960 (I was unaware it was technically Godard's second film and watched it as his fourth) |

Godard's follow-up to "Breathless", banned in France until 1963, may replicate some of its predecessor's motifs (mainly the long-winded conversations between would-be lovers in cheap motel rooms and droptop convertibles) but it is a radical departure in tone and content. If the former was all cinematic posturing and self-aware winks then "Le Petit Soldat" is about the unbearable lightness of being. Michel Subor's Bruno is so staunch in his refusal to adopt an ideal, any ideal, that he allows himself to be tortured rather than pick a side in the Algerian revolution. His obstinate insistence on maintaining a state of neutrality in an increasingly polarized world is masochistic, costing him his friends, his lover and nearly his life. Yes, the many false equivalences in the film between French occupiers and the ALF are troubling and ahistorical but they can be taken, whether intended or not, as reflections Bruno's glib justifications for a living life unencumbered by belief.

It really is impressive how much mileage Godard squeezes out of this attempt to make a minimalist, micro-budget spy film just by shamelessly relying on his heedless love of cinema to carry him through. The voiceover, which fills in the blanks in the narrative whenever the budget comes up short while simultaneously evoking the Hollywood noirs of the 1940's, is so pervasive, occupying nearly every frame of the picture, that it becomes a running joke. An impromptu photography session with Anna Karina (a motif which would surface once again in "Vivre Sa Vie") leads to the much lionized and very Godardian line "Photography is truth, and cinema is truth 24 times per second". A particularly audacious moment features Bruno randomly quoting Raoul Coutard, the film's director of photography, and referring to him as the finest cinematographer in all of France. It may not the shot of adrenaline that "Breathless" was, and its murky tone and facile real-world politics may grapple uncomfortably with its joyful depiction of cinematic artifice, but "Le Petit Soldat" is more than worthy second feature.

|

| 1963 |

"Les Carabiners", Godard's take on the war genre and the fifth different genre he explored in as many films, is an assault on jingoism, propaganda, and the idea that there is anything noble about war or the men who enlist to fight in it. It is his most overtly political film so far and, unlike the rather muddled "Le Petit Soldat", clear eyed about its stance and implications.

Unfortunately, it is also his least interesting film to date. A scene in a movie theater that evokes the way audiences first reacted to the Lumieres' "The Arrival of a Train..." while also paying tribute to the loving fantasy of Buster Keaton's "Sherlock Jr.", is amusing enough on its own terms. And a prolonged sequence involving postcards, undeniably the stand-out moment of the film, is a master class in building humor out of repetition that also serves as an unforgettable illustration of the way history and culture are stripped of their contexts, commodified and sold as facile little fantasies by colonialists. The rest of the film, however, is a repetitive exercise in blunt didacticism.

|

| 1963 |

It is rather amusing that 'Contempt', a film about the behind-the-scenes drama during a movie's production, is probably Godard's least self-referential picture to date. To be sure, it is rife with his typical wordplay, breaks the fourth wall on numerous occasions and features Fritz Lang himself as a prominent character but, with the exception of a few micro-flashbacks (paying tribute to Alain Resnais, perhaps?) and a brief montage with competing voiceover monologues, it is mostly devoid of the flashier, more disruptive elements of his style. The film develops chronologically, the editing is mostly continuous, some attention is paid to character psychology and there is even a touch of unironic classicism in the way landscapes are photographed and used. 'Contempt' feels like an experiment, as if Godard were testing the waters to see if he could operate comfortably within the confines of a big budget, star laden mainstream film.

Yet this is still a profoundly subversive picture. It would have been comparatively easy to make a paean to the triumph of art or a lament to its commodification by greedy producers but lead character Paul, as depicted in the film, is a thoroughly mediocre writer to begin with. For all his knowledge and bluster, he makes his living by writing pepla screenplays and detective fiction. His qualms about accepting a job rewriting a film that is to be directed by Fritz Lang, the consummate cinematic artist, feel performative. He woefully misinterprets Homer's 'The Odyssey' to a degree that is downright astonishing, and his eventual about face, accompanied by a tirade about the sanctity of art and the corrupting influence of money, is treated as a joke. He is every bit as contemptible as bad as Jeremy Prokosch, the villainous producer who hired him in the first place. Godard takes no prisoners in his critique of Hollywood filmmaking.

At its core, however, 'Contempt' is about the dissolution of a marriage. The bulk of the picture is a 45 minute tour-de-force sequence taking place entirely inside the apartment Paul shares with his wife, Camille. As they go about casually performing daily tasks (cooking, bathing, using the restroom), rarely occupying the same space but nonetheless engaged in an extended conversation that endlessly circles around the hurt they share without ever quite managing to breach it directly, Godard uses every inch of the 2:35:1 frame to highlight the growing distance between the pair. The sequence climaxes with an incredible moment in which the camera has to constantly pan between the pair as they talk to one another because their emotional distance has grown to such a degree that, despite the fact they are sitting at a table right across from each other, even the widest of screens is no longer wide enough to fit them both. Such is the magnitude of the chiasm that now separates them. It may well be the standout moment of the film and is certainly one of the standout moments of Godard's career thus far.

Comments

Post a Comment